Innovation

Drawing on humanist social theory, Mexico City codified a universal “right to the city” in a 2010 charter and in its new constitution, ratified February 5, 2017. As stated in the Political Constitution of Mexico City, “The right to the city is a collective right that guarantees the full exercise of human rights, the social function of the city, their democratic management and ensures territorial justice, social inclusion and the equitable distribution of public goods with the participation of citizens.”

Democratic Challenge

For thousands of years people have gathered in cities to create community and opportunity. That collective act of creation, and that sense of belonging, should be equally available to everyone who wants to participate.

How’d They Do It?

The concept of a “right to the city” was articulated in the late 1960s by French sociologist Henri Lefebvre. Lefebvre lamented that cities had become capitalist commodities, governed primarily for private gain. In his alternate vision, the city is a shared space where people come together to forge and negotiate identity, culture and society. The city is ”a meeting place for building collective life.” Or in the words of Mexico City Lab for the City director Gabriella Gomez-Mont, “You create the city and in return, the city creates you.” Whenever individuals and groups are excluded from meaningful participation in this collective act of creation, the right to the city is being infringed.

You create the city and in return, the city creates you.

Gabriella Gomez-Mont, Director, Lab for the City

There have been waves of global activism around the Right to the City from the 1990s onward, attempting to get the right incorporated into the World Social Forum, the World Urban Forum, the United Nations’ urban agenda, and other frameworks. A World Charter for the Right to the City was developed just after the turn of the century, defining the right as “the equitable usufruct of cities within the principles of sustainability, democracy, equity, and social justice.” (Critics have decried these attempts to institutionalize the right within existing governance structures, arguing that this undermines its radicalism.)

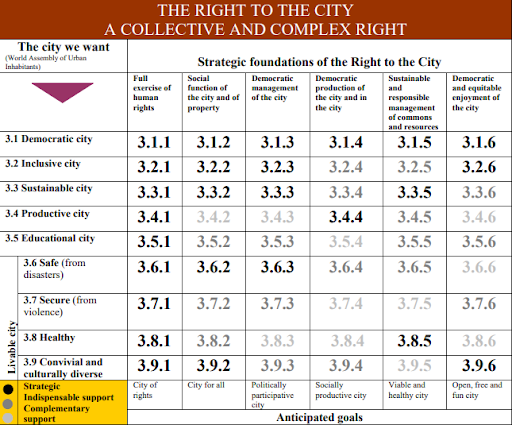

In 2007, activists in Mexico City reached an agreement with the city government to develop a native charter for the right to the city. A three-day public roundtable was held in January 2008 to kick off the effort, and a Promotion Committee was established with government and civil-society representatives to solicit public input and oversee the drafting of the charter. The Committee organized three public events, attracting some 3,000 people, and held more than 30 meetings to coordinate, discuss, and integrate diverse voices and materials. The draft charter was submitted to the city government in September 2009, and the final Mexico City Charter for the Right to the City was adopted in July 2010. It is constructed around six strategic foundations and five descriptors of ‘the city we want,’ (see image) and it concludes with commitments for local government, education entities, civil society, social organizations, the private sector and ‘people in general.’

The Political Constitution of Mexico City, which was approved by and for the newly autonomous federal district in 2017, incorporated the ideas of the Charter for the Right of the City into its Charter of Rights, a section of the governing documents that officially recognizes the rights of all of the city's inhabitants.

How Is It going?

The Right to the City serves as a ‘big tent’ for ideas about citizenship, economic equality, access to services, land use, and other core concerns. In Mexico City, policymakers and civil servants have staked out particular sub-rights including the right to play, the right to imagine, the right to be part of policymaking, and the right to good public administration. These last two rights provide a foundation for diverse initiatives such as participatory budgeting, combating corruption, opening government information, reforms to performance measurements for government staff, and designing for residents with disabilities. “A city has to be equal for everyone,” Political Reform Unit Chief Gustavo Sanchez said. “Everyone must have access to public decisions.” The Social Development Secretary has cited the Right to the City constitutional article as part of the legal framework for its food-security, social-equity and domestic-violence programs, as well as participatory neighborhood and community development.

There are still open questions regarding how the Right to the City will be operationalized, particularly with regard to communities affected by development and taxation. Efforts to include land-value capture in the Mexico City Constitution failed, but the document does require payments from real-estate developers to mitigate environmental and ‘urban impacts.’ Policy and regulation will be overseen by a new Institute of Democratic and Prospective Planning, and a new General Program of Zoning.

A Right to the City

A Right to the City